We’ve all heard people say that God “told them” something.

Most of the time, they’re wrong.

I’m not saying that God can’t interact with our thought processes or, as some folks say, “lay [something] on my heart.” The Spirit who indwells us interacts with us all the time, convicting, teaching, directing, influencing our thinking and our actions.

But that’s very different from saying that God speaks to you, in your head.

I’d like to spend a post or two examining why I hit the off switch when someone tells me that God spoke to him.

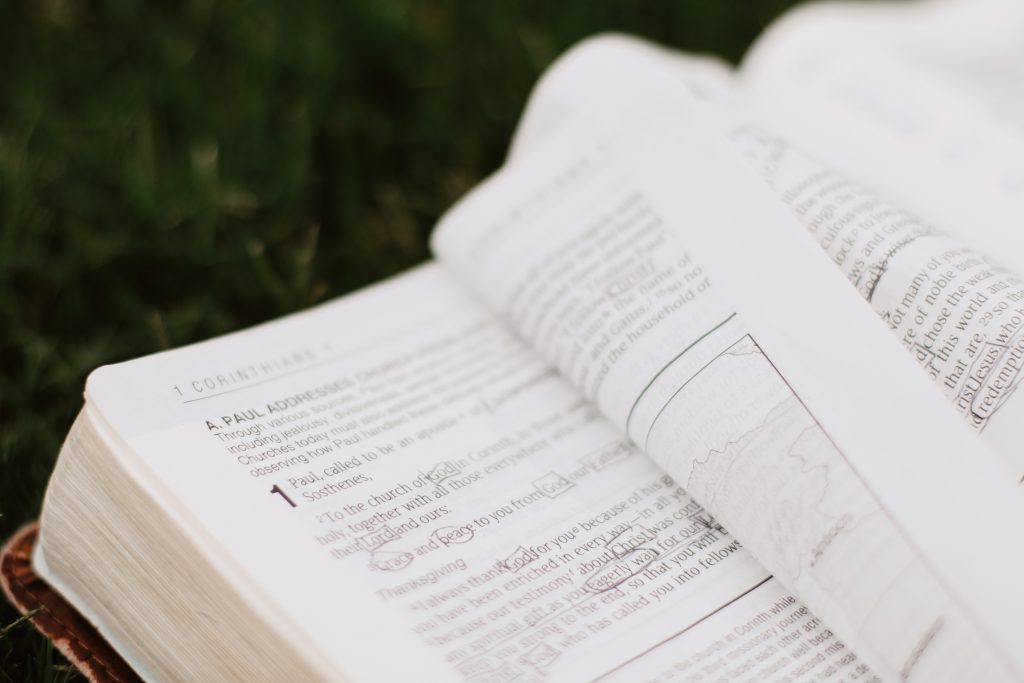

As always, to evaluate this claim we have to go to the Scripture—which is replete with cases of God speaking to people.

God speaks all the time—

- He speaks throughout the biblical timeline, from the very First Day—“Let there be light!” (Gen 1.3) to the very end of the very last biblical book to be written, 60 or more years after the death of Christ—“Surely I am coming soon!” (Rev 22.20).

- He speaks on all sorts of occasions—

- Both formal (in his throne room, Is 6.8) and informal (while Gideon was threshing wheat, Judg 6.14)

- Both happy (the baptism of Jesus, Mt 3.17) and unhappy (Elijah in the wilderness, 1K 19.9)

- Both to encourage (to Paul in prison, Ac 18.10) and to condemn (to the king of Babylon, Isa 14.4-23)

- He speaks in all different sorts of ways—

- In one-on-one conversations

- With Adam (Gen 2.16-17)

- With Noah (Gen 6.13ff)

- With Abram, in the door of his tent (Gen 18.20ff)

- To people who are sleeping, in their dreams

- To Jacob, of the staircase (Gen 28.12ff)

- To Joseph, of his brothers bowing down to him (Gen 37.5ff)

- To Pharaoh, of the coming famine (Gen 41.1ff)

- To Nebuchadnezzar, of the coming kingdoms (Dan 2.1ff)

- To Joseph the carpenter, of Mary’s pregnancy (Mt 1.20)

- To people who are awake, in visions

- To Abram, concerning his offspring (Gen 15.1)

- To the boy Samuel, concerning the death of Eli (1S 3.1-15)

- To Nathan the prophet, about David’s future son (2S 7.4-17)

- To Ezekiel, about the judgment and restoration of Judah (Ezk 1.1)

- To Paul, about heaven (2Co 12.1ff)

- In an audible voice

- A loud one, from Sinai, to the people of Israel (Ex 19.16-20)

- A normal one, to Hagar, when she ran away from Sarai (Gen 16.11-13)

- A quiet one, to Elijah, alone in the wilderness (1K 19.12)

- Through representations of his presence

- A burning bush (Ex 3.1ff)

- A pillar of fire (Ex 13.21)

- A glory cloud—which may have been the same as the pillar of fire (Ex 40.34)

- Urim and Thummim—whatever they were (Ex 28.30)

- A whirlwind (Job 38.1ff)

- An asterism (Mt 2.2)

- In one-on-one conversations

- He speaks to all different sorts of people—

- Prophets, throughout both Testaments

- Wise men, such as Solomon, as in Proverbs

- Rulers, such as Nebuchadnezzar, as noted above

- Ordinary people

- A little boy sleeping in the Tabernacle (1S 3.2ff)

- A peasant woman in a nondescript village (Lk 1.26ff)

- A shepherd on the west side of the desert (Ex 3.1ff)

- And even a donkey! (Num 22.23ff)

So why am I suspicious of people who claim that he has spoken to them today?

Because the same Bible that tells us of all these past revelatory acts of God has also told us that things have changed:

Long ago, at many times and in many ways, God spoke to our fathers by the prophets, 2 but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son (Heb 1.1-2).

The writer of Hebrews, whoever she was ( :-) ), first notes what I’ve delineated extensively above: that God has spoken in many times, in many ways, through many different people.

But, the author says, things are different now.

Now God has spoken through his Son.

This passage is structured as a contrast: God’s revelation used to happen a certain way, but it doesn’t happen that way anymore. Today, God has spoken in Christ.

In Part 2, we’ll talk about how we’re supposed to hear today what he has spoken, and I’m going to try to convince you that the new way is better than the old way—by a lot.

See you then.