It’s not news to anybody that US culture is highly polarized and has been for some time. This polarization shows up most readily in political disputes, and especially in presidential election years, when all the disputes come to a head and when the consequences of victory and defeat are most clearly obvious.

Presidential elections have always been rowdy affairs in this country, at least since Adams v Jefferson in 1796. Some are rowdier than others, of course—Adams/Jackson (1824), Hayes/Tilden (1876), and Nixon/Humphrey (1968) come immediately to mind. Anybody currently over the age of 40 knows that every election since 1992 has been “the most important election of our lifetime.”

Even so, it feels like this year is extraordinary. There’s been fighting in the streets that reminds us old-timers of 1968, combined with a general sense of being on edge due to all the coronavirus issues. Adding fuel to the fire is the fact that with social media, now every nitwit can be a publisher, with no editorial constraints—and we all know nitwits who are taking advantage of the opportunity. And now there’s a third vacancy on the Supreme Court in just 4 years.

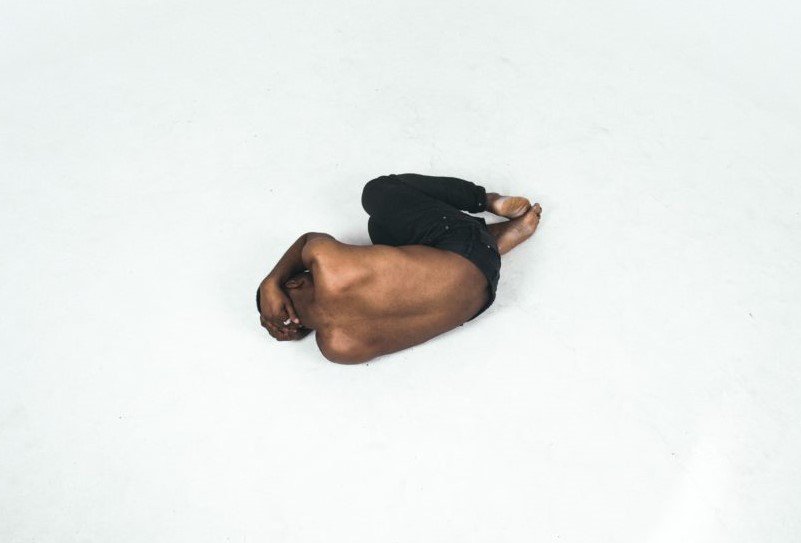

Polarization. Tribalism. And lots of fuel to pour on that fire. Historians know that a key cause of the Civil War was sectionalism, and to them all this is looking pretty familiar. Here the divide is not as clearly geographical as it was 160 years ago—which in some ways makes the situation even worse—but it’s still eerily familiar.

And so there’s open talk about civil war. Red vs blue. Urban vs rural. Liberal vs conservative. And unsurprisingly, the joke about one side having all the guns doesn’t ease the tension.

I’d suggest that the solutions most commonly bandied about aren’t solutions at all.

Force—and the unconditional surrender of one of the parties—isn’t a long-term solution, as World Wars 1 and 2 so clearly taught us. The simmering rage of humiliation eventually breaks out again, and the second time is often worse than the first.

Appeasement doesn’t work either—again, as the World Wars demonstrated. (Think Neville Chamberlain.) When two sides each see the other as the enemy of their aspirations, eventually they’re going to resort to force.

In our situation the problem is compounded by the sheer number of things that divide us. We’re divided by race; by economic status; by political philosophy; by sex. These divisions go to the very core of our perceived identity; we’re not going to compromise them.

We can avoid civil war only by finding some part of our identity that is more powerful than the things that divide us. For many years, our shared identity as Americans was enough to do that. Often it’s the existence of a common threat, as in World War 2 and again for a few months after 9/11. For much of my lifetime there have been those arguing for unity on the basis of our shared humanity—who usually are dismissed as dreamers in the image of John Lennon.

I’d like to suggest that the Scripture speaks repeatedly of something that breaks down the racial and sexual and political and economic barriers that persistently divide us—and, perhaps surprisingly, it is based, in a specific way, in our shared humanity. The Bible doesn’t just dangle this idea out there as a carrot to get the kids fighting in the back seat to finally get along (and, I suppose, to stop mixing their metaphors); on the contrary, it presents the unity of peoples across significant barriers as a central part of the plan of God—something that he not only desires but is applying his divine power to accomplish with absolute certainty: that “God [is] in Christ reconciling the world unto himself” (2Co 5.19), so that “there is neither Jew nor Greek, … slave nor free man, … male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Ga 3.28), toward the goal of “a great multitude which no one could count, from every nation and all tribes and peoples and tongues, standing before the throne and before the Lamb, clothed in white robes” (Re 7.9)—a unity so spectacular, so unimaginable, and so unbelievable even by those witnessing it, “that the manifold wisdom of God might now be made known through the church to the rulers and the authorities in the heavenly places” (Ep 3.10); that is, that even supernatural beings are taken by surprise.

Wow.

There are lots of places in the Scripture where we can read about these ideas. I’ve chosen a section of Paul’s letter to the Colossian church, where I’ve been studying this month. We’ll embark on that study in the next post.

Part 2: Acknowledging the Divide | Part 3: “Great Is Diana!” | Part 4: Letting Hate Drive | Part 5: Pants on Fire | Part 6: Turning Toward the Light | Part 7: Breaking Down the Walls | Part 8: Beyond Tolerance | Part 9: Love | Part 10: Peace | Part 11: Encouragement | Part 12: Gratitude

Photo by Jens Lelie on Unsplash