Let’s take a closer look at Psalm 11, where we find ourselves faced with a stark choice as we deal with troublous times.

Stanza 1 includes verses 1-3. David’s advisors, having done a SWOT analysis, present him with what appears to be the only logical choice: “Run! Run for your life!”

Flee as a bird to your mountain!

And they give solid reasons: you have enemies, and they are preparing for action, which includes hidden threats to your very life. With weapons. Bad ones.

For, lo, the wicked bend their bow, they make ready their arrow upon the string, that they may privily shoot at the upright in heart.

They also note the consequences of inaction.

If the foundations be destroyed, what can the righteous do?!

This is, as we say these days, an “existential threat.” The consequences are world-shaking. What we’re facing is the end of all we know and love. Oblivion.

That’s their case.

Now David presents his.

I note that he doesn’t deny the truth of their facts. He’s not careless, disengaged, distracted, or apathetic. “There are no threats; no one’s after me; you people are a bunch of paranoid freaks.”

No. Accepting their major premise—that there’s a real threat out there—he presents rather a different perspective on it.

He brings in a variable that they haven’t mentioned. There is another actor on the battlefield; his name is YHWH, the ever-present and unchanging one, the one who keeps covenants. David views this God from three different perspectives.

His Person

David begins his response with a statement about who God is, what he is like:

The LORD is in his holy temple, the LORD’S throne is in heaven (v 4).

What is he like? Well, for starters, he has a temple—he’s God—and it’s “holy,” or unique. He’s not like everybody else; he’s in a class by himself. Adding him to the scene changes everything.

Second, he has a throne. That means he’s a king. And if he’s holy, then he’s not like any other king. He’s bigger, and stronger, and smarter, and better at kinging than any other king.

There’s a third factor. That throne is in heaven. That means, at least, that he’s above the battlefield and has a broader and clearer perspective on what’s going on down below. The high ground is militarily significant for many reasons, and one of them is the advantage that its perspective gives for strategic planning.

And heaven, of course, is not just any ordinary high ground. It’s the highest ground of all, the home of him who never loses.

So this is who the fearful have left out of their equation. A fairly significant oversight.

His Perspective

David also considers where God is looking—where his attention is focused. He actually bookends his thoughts—what scholars call an inclusio—with this idea.

His eyes behold, his eyelids try, the children of men (v 4).

His countenance doth behold the upright (v 7).

This powerful God, this master general, this unmatchable force, is paying attention. His eyes are focused like a laser on his people; he knows what’s going on, and his hands are poised on the armrests of his throne as he prepares to move against any and all threats to them. His silence is evidence not of distance or distraction, but of concentration.

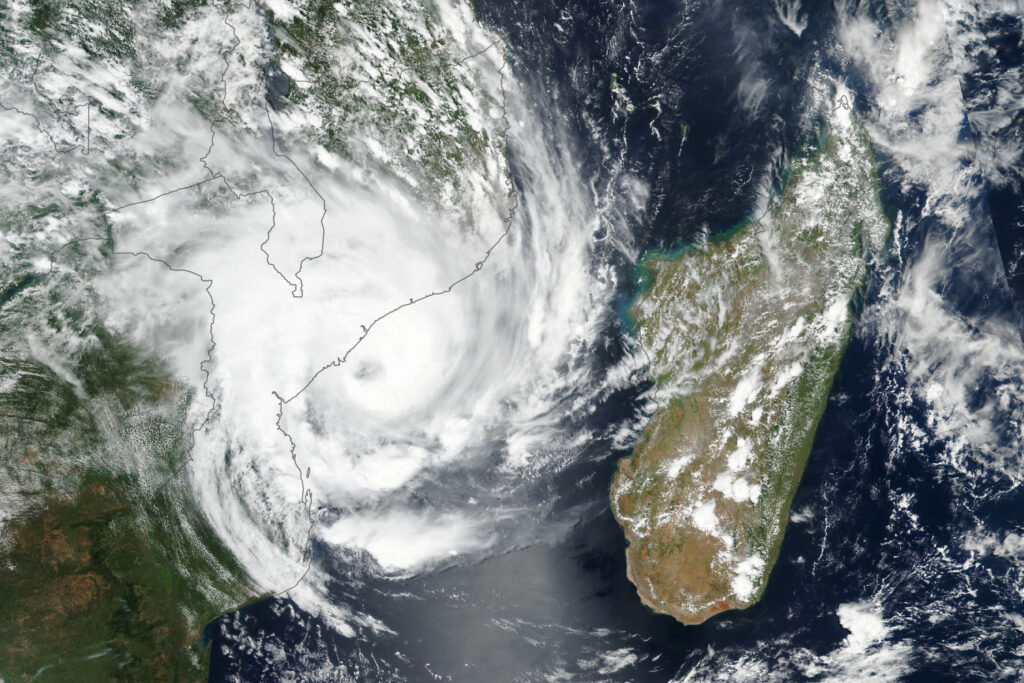

The storm in which we find ourselves has an eye, a place of calm. And the eye belongs to God.

His Plan

God has plans for every actor on the battlefield.

God’s plan for the righteous is to strengthen him not by avoiding the exertion of battle, but by enduring it.

The Lord trieth the righteous (v 5).

We all know that athletes don’t become great by lying on the couch. They become great by building endurance through physical challenges—wind sprints, road work, scrimmages seemingly without end. And they build dexterity and skills by constant repetition at the blocking sled or doing layups or punching the timing bag.

They get tired.

But they get great.

That’s God’s loving plan for us through the dark days, through the frightening challenges (Ro 5.3-5).

God also has plans for those who threaten his people.

The wicked and him that loveth violence his soul hateth. 6 Upon the wicked he shall rain snares, fire and brimstone, and an horrible tempest: this shall be the portion of their cup (vv 5b-6).

They won’t prevail. They won’t even survive.

The foundations, in the end, cannot be destroyed. The battle may well be strenuous, and we may well pick up some Purple Hearts, or maybe even a Congressional Medal of Honor, along the way.

But the outcome is certain.

Fear not.

Photo by NASA. That’s Tropical Cyclone Eloise coming ashore in Mozambique on January 22, 2021.