Introduction | Song 1, Part 1 | Song 1, Part 2 | Song 2, Part 1 | Song 2, Part 2

Now God’s reply to the Servant points him to the outcome of his assuredly successful mission: the eternal deliverance and joy of the people he is serving.

With perfect timing, God is already hearing and helping his Servant, and he will continue to do so (Is 49.8). For the rest of the Song he appears to be focusing on the Servant’s work with Israel rather than the Gentiles; note the phrase “covenant of the people” (cf. Is 49.5-6 and “his people” in verse 13)—though he does speak briefly here of the “establish[ment of] the earth.”

He has much to say about the outcome of that work.

He will return Israel to the land of its inheritance, which is currently desolate. We should note that while Isaiah is writing in the 700s BC (probably just before the Assyrians deported the leadership of the Northern Kingdom, Israel), his primary audience appears to be Judah, the Southern Kingdom, as they will experience captivity in Babylon some 150 years later. (Perhaps the clearest indication of this is his naming of Cyrus, the Persian who overthrew Babylon, in Is 44.28 and 45.1.)

So I think that here he is speaking to the Jews who will be exiled in Babylon, predicting their release and return from captivity. It is they who will reinhabit their currently desolate Promised Land (Is 49.8), who will be released from captivity and return to lush pasturelands (Is 49.9). They will live in comfort, out of the heat of the sun and next to an ample water supply, because the Lord will show mercy—end their deserved punishment—and lead them home (Is 49.10).

In language reminiscent of the famous passage in Isaiah 40—“make straight in the desert a highway for our God. Every valley shall be exalted, and every mountain and hill shall be made low”—God promises that the road home will be smooth and straight (Is 49.11). God’s people will flow back to their land from the far corners of the earth (Is 49.12).

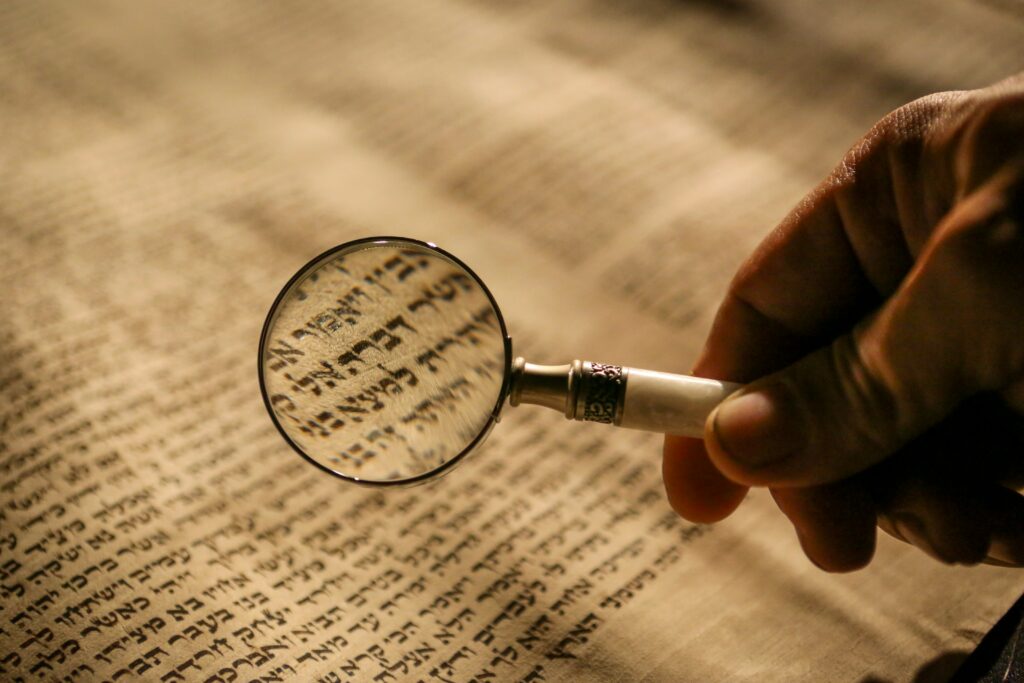

Here we see hints of something more than the return of Judahites from Babylon. Those returning from Babylon would naturally approach Israel from the north, as they follow the water supply of the Euphrates River along the Fertile Crescent. But some are said to come from the west—and since Israel’s western border is the Mediterranean Sea, I would assume that this would refer to people coming from the Mediterranean Basin. And then there’s the reference to “the land of Sinim.” To be frank, nobody knows where that is. Some aggressive interpreters see the root “Sino-,” which is used in the modern age to refer to China, but the Bible nowhere uses the term in this sense; indeed, this is the only occurrence of the word in Scripture. Some have suggested Syene, on the Nile in southern Egypt. Or it may be noteworthy that during the Wilderness Wanderings Israel spent time in “the Wilderness of Sin” (Ex 16.1; 17.1; Nu 33.11-12), somewhere south of the Land. But in the end, nobody knows. The most highly regarded Hebrew lexicon (HALOT for you Hebrew nerds) says simply, “unknown.”

The Song ends with a doxology (Is 49.13). Heaven and earth are called to praise God with singing, for he “hath comforted his people, and will have mercy upon his afflicted.”

This Second Song, then, notes the Servant’s apparent unimpressiveness, an idea that we’ll come across again in the remaining Songs. Yet it assures the Servant—and us—of his exalted status, even apparently ascribing deity to him, even as it assures us that his people, both Jewish and Gentile, will eventually live in a changed world, one changed significantly for the better.

We see a phenomenon here not uncommon elsewhere in prophecy, where there’s a near-term prediction (in this case, Judah’s return from Babylon) but also wording that seems to call for a fulfillment much farther into the future, even in the eschaton.

We’ll turn next time to the Third Song, the shortest one.

Photo by Mick Haupt on Unsplash

Song 3 | Song 4, Part 1 | Song 4, Part 2 | Song 4, Part 3 | Song 4, Part 4 | Song 4, Part 5