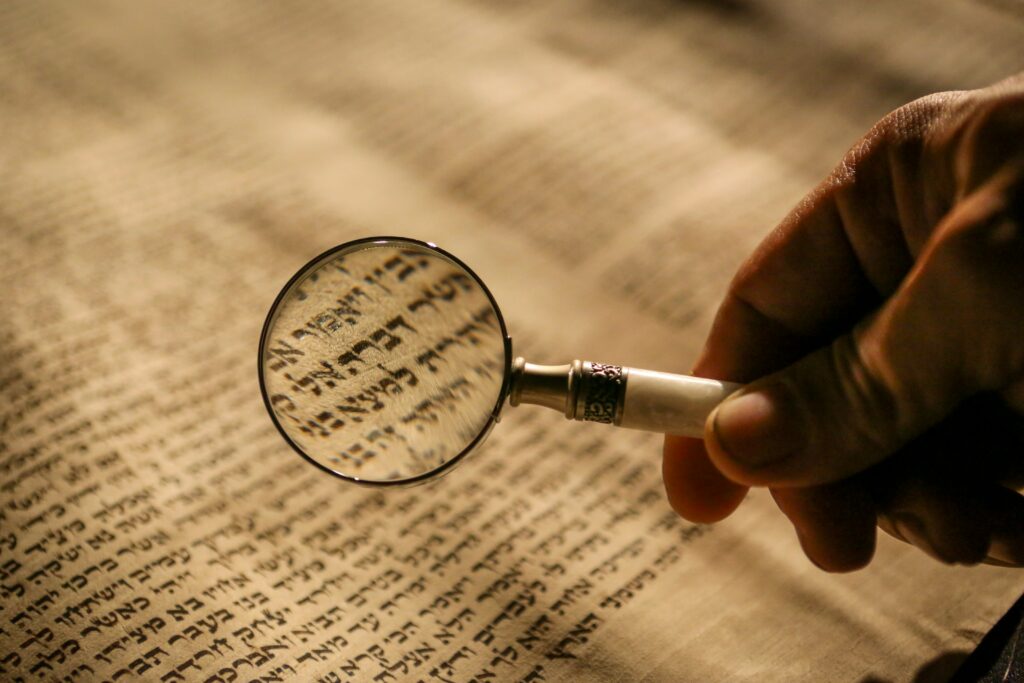

Isaiah’s first Servant Song appears at the beginning of chapter 42. There’s some disagreement among scholars as to where precisely it ends; in fact, the precise references of all the Servant Songs are somewhat fuzzy. For the first song, many would limit it to the first 4 verses, while others would take it through verse 9—in which case the song has a second stanza. I decided to memorize the longer passage, so we’ll take two posts for this song, one for each stanza.

This first stanza is in the voice of God, addressing Isaiah’s audience (note the plural “you” in Is 42.9) and referring to the Servant in the third person: “Behold my servant” (Is 42.1). God begins describing with affection, in relational terms:

- God’s soul delights in him (Is 42.1).

- God has put his “spirit” upon him (Is 42.1).

I find it interesting that God speaks of both his own soul and his own spirit. Now, since God is not a human, the question of trichotomy—is he body, soul and spirit, or just body and soul?—does not apply to him. I’d suggest, then, that his use of both terms together may suggest that he is “all in” in his relationship with the Servant.

Would it be reading the New Testament back into the Old to find a trinitarian implication here?—that the soul is that of the Father, and the spirit is the distinct person of the Holy Spirit? That would lead us to conclude that the Servant is the “missing” third person of the Trinity, the Son.

My background in biblical theology inclines me to be cautious about seeing too much later revelation here, centuries before the incarnation, so I’ll leave that question open.

The rest of the stanza speaks of the Servant’s task—his calling, if you will—and the manner in which he carries it out. Note the repeated theme of justice:

- “He shall bring forth justice to the Gentiles” (Is 42.1);

- “He shall bring forth justice unto truth” (Is 42.3);

- He shall “set justice in the earth” (Is 42.4).

The Servant’s primary task, apparently, is to overturn the injustice of the world system and make it a place where justice is done. We’re not told yet how he will do this, but those of us who’ve read the rest of the story can see easily where this is going.

The stanza ends with several descriptors of the Servant’s manner. We find that manner surprising, for a couple of reasons. First, he’s presented as mild-mannered; and frankly, mild-mannered approaches don’t typically overturn injustice, especially given the commitment of world rulers to maintaining their own power structures. But this one

- will “not cry, nor lift up, nor cause his voice to be heard in the street” (Is 42.2);

- “A bruised reed shall he not break, and the smoking flax shall he not quench” (Is 42.3).

A second surprise comes when we read the third description of his manner:

- “He shall not fail nor be discouraged” (Is 42.4).

This seems to come right out of the blue. Here is someone who has God’s spirit upon him, who is called and empowered to overturn unjust earthly power structures and establish justice all across the earth, reorganizing even Gentile states (Is 42.1), the “isles” (distant coastlands) over which “his law” shall reign (Is 42.4)—so why would we be concerned that he might fail or be discouraged? Where did that come from?

In this first stanza of this first Servant Song, then, we find that the Servant is empowered by God, and in a special relationship with him, and therefore able to do world-shaking things in the cause of justice. Yet, in some way, we’re supposed to be surprised by that. This is a theme we’ll see again in the Songs.

I can’t fail to mention that this stanza shows up in the New Testament, in reference to Christ’s earthly ministry, and specifically in connection to what scholars call the “messianic secret.” Jesus sometimes tells his followers, and the recipients of his miracles, not to tell anyone what he has done. Matthew tells us that he did that in order to fulfill the prophecy of this stanza (Mt 12.15-21); part of his mission, apparently, is to appear not as a conquering king, but as someone who seems not to have any likelihood to be who he really is.

Why? Well, we’re not told. But it occurs to me that God delights in those who come to him by faith, and it doesn’t take much faith to trust in a conquering king on a white stallion. But a Jewish carpenter? from Nazareth (Jn 1.46)? Now, that’s another story.

Photo by Mick Haupt on Unsplash

Song 1, Part 2 | Song 2, Part 1 | Song 2, Part 2 | Song 2, Part 3 | Song 3 | Song 4, Part 1 | Song 4, Part 2 | Song 4, Part 3 | Song 4, Part 4 | Song 4, Part 5