Introduction | Song 1, Part 1 | Song 1, Part 2 | Song 2, Part 1 | Song 2, Part 2 | Song 2, Part 3 | Song 3 | Song 4, Part 1 | Song 4, Part 2 | Song 4, Part 3 | Song 4, Part 4

The final Servant Song ends with a look ahead to the long-term consequences of the Servant’s work (Is 53.10-12). These consequences are two: the satisfaction of the sin debt, and the deliverance of the sinners.

Isaiah states the first consequence in a surprising way: “it pleased the Lord to bruise him” (Is 53.10). Surprising is too soft a word; this is shocking, repugnant. Why would God be pleased to injure his righteous Servant? What is he, some kind of sadist?

No.

Sadism is by definition a pathology, a deviation from truth and goodness and justice. It is the opposite of the character of God. I think there are two factors that refute the charge. First, Isaiah has already filled this Song, as well as the three others, with irony and consequent astonishment and wonder. It is certainly ironic that a good God would allow a righteous Servant to be abused in such a way. Why would he do that? How does this make sense? What’s going on here, anyway?

So this statement is a continuation of the theme of irony, the fact that we, and the prophet himself, are having difficulty making sense of a plan that is beyond our information and comprehension. We are seeing the work of someone far beyond us.

The second factor is the nature of God himself. He knows things that we don’t, and he, being unbound by time and space, plans things for eternal and infinite outcomes. He knows what he’s doing, and he does all things well.

Don’t believe that? You are free not to, of course. But your distrust says far more about you than it does about God.

So, back to our text.

What is happening to the Servant, who, despite his own questions, trusts God, is something that God, with his knowledge and understanding, takes delight in, because of what it’s accomplishing, as well as what it’s revealing about both him and his Servant. Justice—God’s justice—will be satisfied, as the Servant bears the sin of many.

The second consequence, the deliverance of sinners, is stated in several ways. The Servant “shall see his seed.” As we noted in the previous post, there’s a translation question back in verse 8. The KJV renders a clause there as “Who shall declare his generation?” If that’s the better rendering, then this clause answers that one. The Servant will indeed have offspring, millions of descendants, to whom he as a sort of spiritual father has given life. He shall see his seed. He shall justify many, delivering them from death, both physical and spiritual.

Like a victor claiming the spoils of a defeated enemy, he will be enriched by a generation of those whose sins he has borne, for whom he has interceded.

And that is why the all-seeing, all-knowing God delights in his Servant’s admittedly gruesome work. It is parallel to what we, his people, are called to do: suffer for a while, bearing a relatively light burden, for eternal values: grace, mercy, and peace, to the ages of the ages.

We servants have such a Servant as our deliverer. His faithfulness enables our fruitfulness.

This Servant is indeed one who sets justice in the earth, a covenant of the people, a light to the Gentiles. He is one who brings out the prisoners from the prison, and those who sit in darkness out of the prison house. One who glorifies God and is made glorious by him, who is his salvation unto the ends of the earth.

We shall not hunger or thirst, nor shall the heat or sun smite us; for he who has mercy on us shall lead us, even by springs of water.

Mountains will become highways, for the Lord has comforted his people and has had mercy on his afflicted.

Hallelujah.

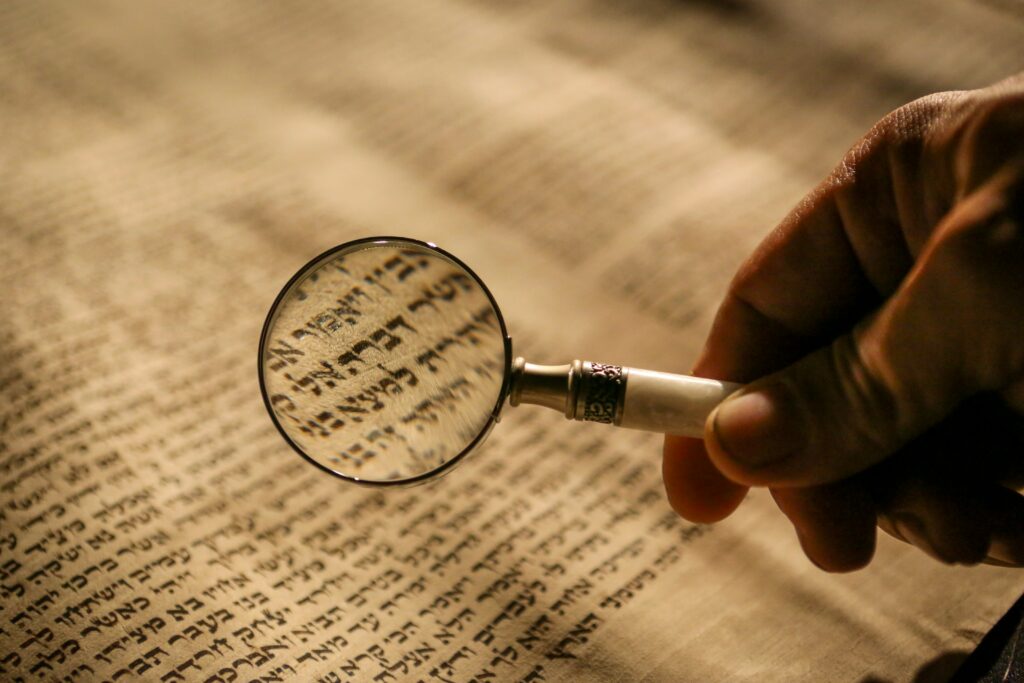

Photo by Mick Haupt on Unsplash