I missed a couple of blog postings last week. During that time I had an experience that refreshed my thinking about providence. Today’s the day I share it.

One of my major concerns over the last few years has been what to do with my physical library. I knew that when I retired I’d lose my comfortable shelf space in my office, and there’s no way I can move all those books into my house. Further, I hardly use them anymore and haven’t for years; virtually all my study and other reading is electronic, for a couple of reasons. First, almost all of what I need access to is now available in electronic form, and my Logos library and Kindle library are more than sufficient for my needs, even before retirement. Second, in electronic form I can make the type bigger, whereas many of my physical books I now struggle to read.

For a few years I’ve been offering my books to my students; come on by my office, I say, and take whatever you want. But hardly anybody’s interested; their reading is electronic too, and like me they don’t want to lug heavy boxes of books around every time they move.

So what to do?

I sent a bunch of them to West Africa Baptist College in Wa, Ghana, where I’ve taught several classes. I also knew that Central Africa Baptist University in Kitwe, Zambia, was compiling a very good theological library, and I was planning to send everything else over there, but I couldn’t get it all together before the shipping deadline.

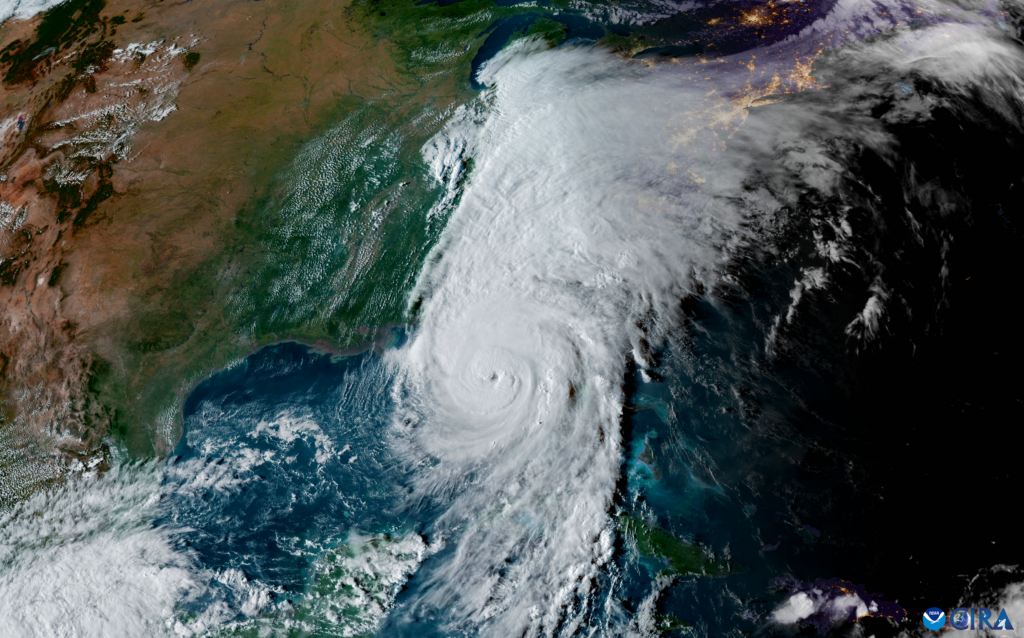

Then I heard from a friend who works for Operation Renewed Hope that a church in eastern Tennessee was flooded during Hurricane Helene, and both the pastor and his assistant had lost their entire libraries.

Well, maybe they could use mine.

So when school ended I packed my books into 23 heavy boxes—I estimated close to half a ton—and, on a day convenient to both the church and me, loaded them into my van. (Boy, do I love Stow-‘N-Go seats!) Earlier I had mentioned to a retired pastor in my church what I was planning, and he offered another 8 boxes, maybe 400 pounds, of really good books as well.

The convenient day was Thursday, June 19. (Yep, Juneteenth. A good day for giving.) The evening of the 18th I saw a news report that a rockslide and flooding had closed I-40 on the NC/TN state line. That was by far the most efficient route. After a couple of text exchanges, I opted for I-26 north (officially west) to I-81 and then south into eastern Tennessee. That would add an hour to the trip each way, but I considered that a minor issue.

The wife and I set out at 7.30 Thursday morning, with the sun shining, a full gas tank, and almost a ton of books. North to Asheville and its morning rush hour, then north through the beautiful mountains and valleys of northwestern North Carolina, all the way to Johnson City, Tennessee (which isn’t all that far from Olinger, Virginia, and the Olinger Baptist Church, but that’s another story).

Heading southwest on I-81, we ran into the hardest rainstorm I’ve ever driven in. It was astonishing. Traffic slowed to under 40 mph, and with everybody’s wipers and flashers in action our little line of vehicles managed to come out on the other side no worse for the wear.

Then south a few miles on winding country roads to the church. It sits literally just across the street from the Pigeon River, which dominates that part of the state and is large at this location. I could just imagine what it looked like during the hurricane, surging out of its banks and overwhelming everything in its path.

The assistant pastor was waiting for me. When he told me his name, it startled me; he looked just like someone else I know by that name. I stared stupidly at him for a few seconds, then asked, “Are you related to [person with this name, and meeting this description]?” He laughed. “That’s my Dad.” Well, that means his Mom used to work with me at BJU Press, and he’s the nephew of two personal friends, including a member of my deacon care group at church. I had no idea that I had any connection with anyone at this church.

So a portion of my library is going to a family I treasure.

Cool.

Helene brought a lot of suffering to a lot of good people. There’s no minimizing or dismissing the depth of that suffering.

But all along the way God cares for his people and places little lights that remind us that he’s there.

Photo credit: Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere at Colorado State University and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration