We all love the underdog. We cheer for David against Goliath. We love it when the cocky athletic novice gets a whoopin’ from the aging veteran of the sport.

But we don’t like it when the roles are reversed, when we’re the one who’s humiliated.

The Bible gives examples of people getting humiliated. We can learn from them.

Pharaoh

We all know the story of Moses before Pharaoh. Moses appears in his court and delivers the message from God: “Let my people go” (Ex 5.1). Pharaoh’s reply is terse and pointed:

“Who is the Lord that I should obey His voice to let Israel go? I do not know the Lord, and besides, I will not let Israel go.”

We’ve always known how the story turns out—Pharaoh is The Bad Guy. But just as a thought experiment, put yourself in Pharaoh’s sandals. You’re the most powerful man in the world. If you say someone dies, he dies. You tell neighboring kings you want their treasures, and they give them to you. Maybe you know that this Moses was raised in the court 40 years ago; maybe you don’t. But even if you do, you know he’s been keeping sheep in the desert ever since. He’s a has-been, a one-hit wonder who’s now eking out a living playing at county fairs and trying to relive the old glory. And his god? Why should you be impressed with him? What has he done?

But as I say, we all know how the story turns out.

God takes on the gods of Egypt, one by one—starting with the Nile—and in 9 plagues demonstrates that he is greater than them all. And then he turns toward Pharaoh himself and kills his firstborn, the heir, at midnight. And the families of the kingdom are too busy mourning their own loss to mourn his.

He lets God’s people go.

Nebuchadnezzar

There’s another example.

Eventually, as they all do, Pharaoh and his kingdom wane, and another kingdom rises. Babylon defeats Egypt at Carchemish, and Nebuchadnezzar becomes the most powerful man in the world. He builds a capital city on the Euphrates, including an artificial mountain—reportedly for his wife, who missed the mountains of her homeland—with water pumped to the top to supply a waterfall. He stands on the 300-foot-tall wall of the city (that’s what Herodotus says, anyway) highly impressed with himself:

“Is this not Babylon the great, which I myself have built as a royal residence by the might of my power and for the glory of my majesty?” (Dan 4.30).

Again, put yourself in his shoes. He’s telling the truth; no one can dispute it.

But God faces no one mightier than himself. “While the word was in the king’s mouth” (Dan 4.31) Nebuchadnezzar lost his mind, spending the next seven years as the crazy guy down the street, sleeping in the woods and eating grass off the lawn of the county courthouse.

It’s a tribute to Nebuchadnezzar’s personal power that seven years later, when he walked into the palace and said, “I’m back,” everybody apparently agreed. This only increases the contrast between Nebuchadnezzar’s power and that of God, who brought him down in an instant.

Uzziah

One more example, perhaps less well known.

Judah’s king Azariah, or Uzziah, is one of the most successful. He becomes king at 16 and reigns for 52 years (2Ch 26.3)—a veritable Queen Elizabeth (either one). He’s successful in war, and in economy, and in foreign affairs. He’s good at what he does.

One day he decides that if he’s the king, he can be a priest as well.

Now, in God’s design, only two people could be both priest and king. The first was Melchizedek, king of Salem and priest of the Most High God (Ge 14.18); the second is the One for whom Melchizedek’s order was created, the Son of God, king of kings, Jesus Christ (Ps 110.4).

Uzziah’s very badly out of line.

As he had done with Pharaoh and Nebuchadnezzar before him, God reaches out and takes Uzziah down. Leprosy breaks out on his forehead—where everyone can see it—and Uzziah lives as an isolate and outcaste for the rest of his life (2Ch 26.19-21).

Would you like to get crushed? There’s a way to do that.

Promote yourself. Rejoice in yourself. Live for yourself.

And God will bring you down.

Pride goes before destruction,

And a haughty spirit before stumbling (Pr 16.18).

Therefore humble yourselves under the mighty hand of God,

that He may exalt you at the proper time,

casting all your anxiety on Him, because He cares for you

(1P 5.6-7).

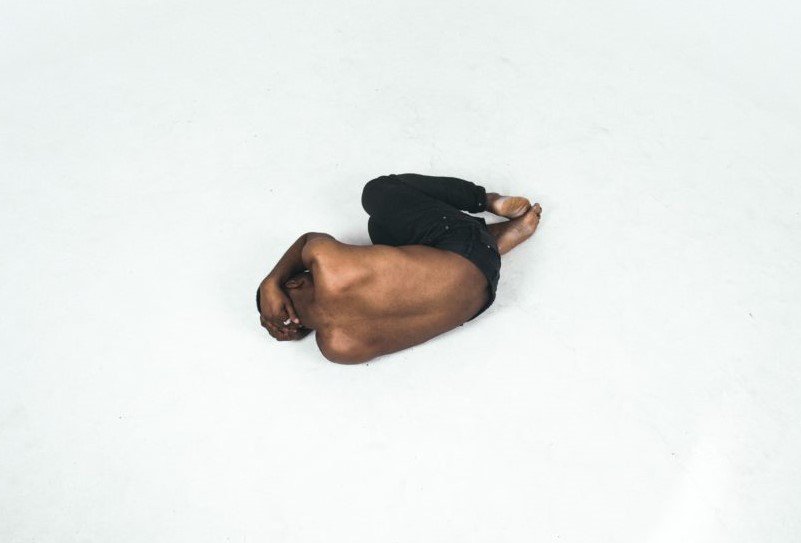

Photo by mwangi gatheca on Unsplash