Part 1: Background | Part 2: Loyal Love | Part 3: Chance | Part 4: Abundance | Part 5: A Plan | Part 6: Approach | Part 7: Proposal | Part 8: Affirmation

True to his word—and to Naomi’s prediction—the next day Boaz sets out to clear up the ambiguity of the situation. “The town gate [Ru 4.1] was the center for social and economic life in ancient Israel. This was where news was first heard, where local and traveling merchants sold their wares in the cool shade of the town walls, where soldiers were stationed, and where legal disputes were handled” (WBH). Essentially, Boaz drops by City Hall to get the business taken care of.

“The word … ‘Behold,’ which begins the second sentence of v. 1 …, serves two functions: expressing Boaz’s surprise at [the nearer relative’s] appearance and turning the reader’s attention to a new character in the drama” (NAC). As Boaz is waiting to conduct his business, here comes the very man who is more nearly related to Naomi. What are the odds?

About the same, I guess, as the odds that Ruth’s “chance chanced” on the field that Boaz owned (Ru 2.3).

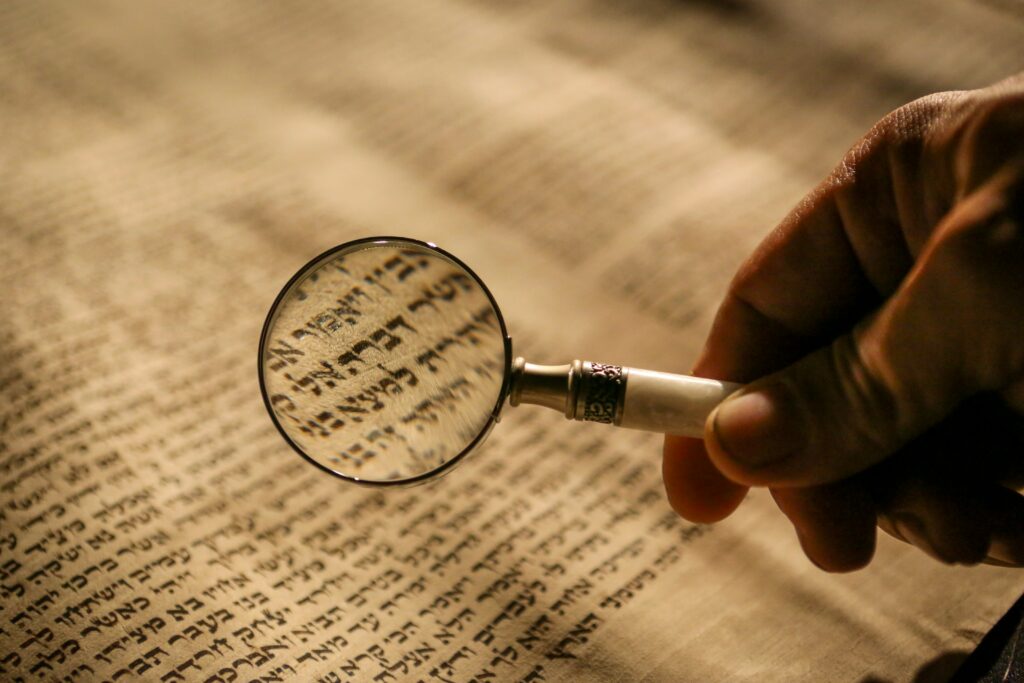

Boaz calls to him. Our modern versions give his address term as “friend,” but the word in the Hebrew (peloni ‘almoni, for you Hebrew nerds) is much richer than that. The KJV renders it “such an one,” which hints at this deeper significance; you don’t call somebody “such an one,” even in 1611. The author has edited Boaz’s words so as to protect the identity of this man. “Rabbinic writings used the designation for an unknown ‘John Doe’ ” (BKC). “The rendering ‘Mr. So-and-so,’ found in the NJPS, certainly captures the sense better than the NIV’s ‘my friend,’ but our ‘Hey you’ also works in the present context” (NAC).

Why would the author of the narrative want to disguise his identity? We’ll see in a moment.

Focused on his purpose, Boaz calls a meeting of the city council—“ten men of the elders of the city” (Ru 4.2).

“Private ownership of land was a jealously guarded privilege in ancient Israel, a right which was proudly handed down within the family. Women were normally excluded from inheritance rights, however, and in no known circumstances were women allowed to inherit their husband’s estates. Naomi may have received income from the sale of Elimelech’s estate, but she probably was not allowed to retain title to the land. The nearest surviving male member of the family would inherit the first option of purchase (Num. 27:7–11)” (TBC).

The unnamed man is initially open to redeeming Elimelech’s land. But then Boaz tells him “the rest of the story” (Ru 4.5). Did he initially withhold this part intentionally? We’re not told, but we do know that Boaz is pretty sharp as a businessman.

“Boaz argued that the nearest kinsman had a moral obligation to keep Elimelech’s line alive. This would involve marrying Ruth and raising a family under his name. In such a case title to the land would eventually revert to Ruth’s children. Under such circumstances, the kinsman hastily renounced his rights as next of kin” (TBC).

“Redeeming the land by itself would have been a good investment because the land would be inherited by the redeemer’s own children. But redeeming Ruth with the land would result in its being left to Ruth’s offspring (for the line of Elimelech). Any resources spent on redeeming the land and raising the offspring would damage his own children’s inheritance since it would benefit the line of Elimelech” (FSB).

“Mr. So-and-so” steps back from his legal obligation. Hence the absence of his name. And now “the generosity of Boaz in accepting these financial losses becomes the more apparent” (NBC).

They conduct a legal ceremony involving an exchange of So-and-so’s sandal (Ru 4.8). “Footwear often symbolized ownership in Bible times. Note … God’s directive to Abraham, Moses, and Joshua to claim ownership of Canaan by walking on it (Gen. 13:17; Deut. 11:24; Josh. 1:3)” (WBH).

Boaz calls the bystanders to bear record (Ru 4.9). (And here we learn that Mahlon was the brother who had been married to Ruth [Ru 4.10].)

Why was Boaz so persistent in showing covenant loyalty to this Moabite woman? He might have had a family reason. “According to Matthew 1:5, Boaz’s mother was Rahab, the Canaanite harlot from Jericho. However, Rahab lived in Joshua’s time, about 250–300 years earlier. Probably, then, Rahab was Boaz’s ‘mother’ in the sense that she was his ancestress (cf. ‘our father Abraham,’ Rom. 4:12)” (BKC).

Next time, the end of the story—and the beginning.

Photo by Paz Arando on Unsplash