I’ve made the decision to retire.

Over the years I’ve thought about when would be the best time to do that. My university turns 100 at Commencement 2027—just a couple of years away—and that would make sense. Shortly after that, after the fall semester in 2027, I would reach 50 official years of service, and that would make sense too.

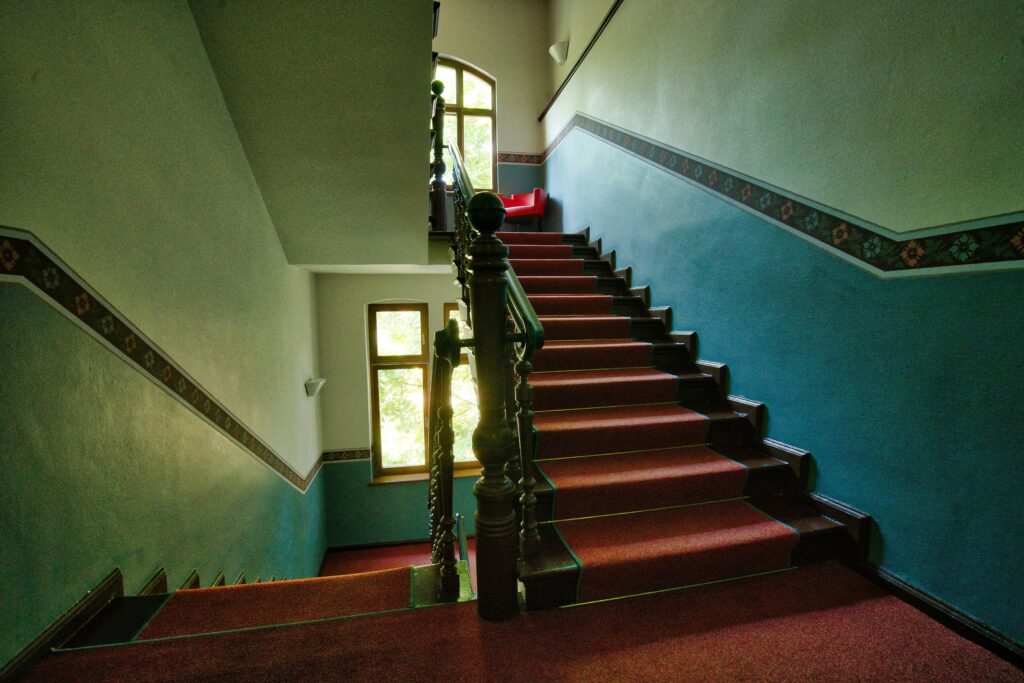

But in the last few years I’ve noticed that my ability to produce is declining. I have increasing difficulty hearing my students’ questions, especially when the air circulation fans are going, even though I have hearing aids—good ones—and wear them all the time. My eyesight is also getting fuzzier, even with glasses, and I have trouble recognizing my students even at a middling distance. I also have difficulty looking toward a light source—I noticed it first at night, and I even got a pair of those polarized yellow “sunglasses” that they advertise to people my age on social media. They help—at night—but they don’t really solve the problem. The other day a student greeted me in the hallway; he was standing in front of a window on a sunny day, and I called him by another student’s name, based on his blond hair; I couldn’t distinguish anything about his face.

So my effectiveness as a teacher is being affected. I think my work is still good enough, but I can see the handwriting on the wall—if it’s big enough and isn’t right next to a window. Mene, mene, tekel, upharsin.

As I’ve been meditating on these things, this year my university is needing to reduce its faculty count—which means that if I retire, that’s one less younger, highly qualified faculty member they’ll have to let go.

My family’s financial situation is appropriate for retirement.

I’m 70.

It’s time.

That decision brings with it a lot of contemplation and rememberizing, of course. I’ve been on the same campus for 52 years, and virtually every location brings back specific memories.

Four years as an undergraduate, first in humanities (because I had no idea what I was doing) and then in Bible. Then I left, expecting to have to work for a year or two to earn money for graduate school. But exactly in the middle of the summer, I got a letter from the famed and sometimes feared Dr. Guenter Salter, Dean of the College of Arts and Science, offering me a grad assistantship in English. (That actually makes more sense than it may sound. Freshman English was 2 semesters of grammar and composition, and as a Greek minor, I had more grammar than the English majors, who spent a lot of their time in literature.)

So five years as a GA, learning the terminology of English grammar rather than Greek—I learned that a “gerund” is just a substantival use of the participle—grading freshman themes, doing some lecturing, and taking 90 hours of Seminary work for a PhD. Then 19 years on staff at the University Press, as an editor (thanks to all those freshman themes), then an author, then an authors’ supervisor, and finally, briefly, manager of strategic planning.

Toward the end of those 19 years I began to get restless. I was using the PhD skills to some extent, but not to their fullest; my responsibilities included a lot of other stuff too. The Bible faculty was solid and stable.

One day I thought, maybe I should go teach someplace else.

The next day Dr. Bob Bell, the Seminary’s curriculum rabbi, stopped me at lunch and asked if I was interested in teaching.

Sure was. So 25 years on the faculty, eventually settling into 18 years as the chair of the undergrad division, working under and alongside remarkable, godly, competent men and women.

That makes 53 years here, with 47.5 years of official employment. (Undergrad doesn’t count, and GA years get half credit.)

It is enough, in the most positive sense of that clause. The Lord gives good gifts to his people, and he gives them abundantly.

So what’s next?

Don’t know. I’ve done some thinking about it, but I haven’t finalized my priorities yet. Here’s a start:

- Enjoy a more flexible time with my wife, and stay out of her way :-) when appropriate.

- Spend time with our grandson, who lives in town.

- Exercise faithfully.

- Offer my skills at BJU and at church, as desired and appropriate.

- Leverage my flexible schedule for other kinds of service as they may come up.

- Keep the mind sharp, as much as possible. My Dad presented with dementia at 85, so I’ll be keeping an eye on the passage of time. I suppose I could do that in a couple of ways—

a. Read, read, read. Especially long reads. And stuff I’m not already familiar with. New things.

b. Write. Got a few ideas, but nothing firm. FWIW, I do intend to continue the blog on its current schedule.

I even told ChatGPT to read my blog site and suggest possible retirement activities. It came up with a few ideas that I hadn’t.

So we’ll see how it goes, and we’ll revel in the flexibility.

Hallelujah, in its original sense.

Photo by Stefan Steinbauer on Unsplash