Recently I preached in chapel for BJU Seminary. Here’s a summary of that message.

This semester in chapel, BJU Seminary is working through 1 Peter under the theme “Exiles with Expectant Hope.” Peter begins this letter, which is going to talk a lot about suffering and persecution, by pointing out the confident expectation that God’s people have of an inheritance “reserved in heaven for you” (1P 1.4). And this despite the undeniable fact of “manifold testings” (1P 1.6), which, he says, are not a sign that anything has gone wrong with God’s plan for us, but rather are the very means God is using to prepare us for future eternal service that brings glory to God (1P 1.7).

And then, suddenly, Peter puzzles us, on two counts: 1) what he says in verses 10-12; and 2) why he says it at all in this context. What’s his point?

Do you like puzzles? Let’s work on one.

What Peter Says

Peter says, quite surprisingly, that at certain times the Hebrew prophets did not understand the messages they brought from the Lord. Why is that surprising? Because the prophet’s whole job is to bring a message from God to a given audience—Israel, Judah, occasionally one of the neighboring countries. How can he do that if he doesn’t understand the message? What’s he going to say?

I suppose, to be thorough, we should look for specific examples of puzzled prophets in the OT. The one that comes most immediately to my mind is in Daniel 12, where Daniel is given a message from God, through a messenger, apparently in a vision. He sees two men, one on each side of a river (Da 12.5), one of whom asks a third person, “When does the end come?” (Da 12.6). He answers, “A time, times, and a half” (Da 12.7).

Do you find that perfectly clear? I certainly don’t. (I know, several interpreters see that as 3½ years, or half the tribulation period—but I’d suggest that all these years later, the whole thing’s still pretty obscure, as is evidenced by the fact that believers hold any number of eschatological positions.)

As further evidence, I note the very next verse, where the prophet himself says, “I heard, but I understood not.” You too, huh, Daniel?

So he does the reasonable thing and asks for an explanation—he repeats the original question.

And the angel says (this is the Olinger Revised Version), “Never you mind, fella.” He asks for clarification—and is refused!

Why?

The messenger tells him this much: “It’s not for now; it’s for later” (Da 12.9).

And then the book ends.

Whaaat?!

Well, whatever else we think about this specific prophecy, we have confirmation that Peter is not exaggerating. Here’s at least one case where the prophet does not understand the prophecy he’s given.

Are there others?

I don’t know of any others that are specified as fitting the pattern—though Ezekiel’s wheel vision comes pretty close—but I can think of several that the writers might not have understood:

- Did Moses, writing Genesis and describing the Fall event in chapter 3, understand that very odd phrase “the seed of the woman” (Ge 3.15)? Adam and Eve almost certainly didn’t, given that at the time there hadn’t been even one baby born yet; but what about Moses, maybe two or three millennia later? Did he think, “Hmmm. virgin birth?”

- Did Isaiah, seven centuries after Moses, understand when he wrote, “He shall make his grave with the wicked, and with the rich” (Is 53.9)? Is there any chance at all that he could have described with any degree of accuracy what would eventually happen?

We don’t know for sure, of course, because the Bible doesn’t specify, and we know that God doesn’t like it when we say he said things that he didn’t (e.g. Jer 14.14). But deep down inside, I doubt that they understood.

Next time: what specifically they were puzzled about, and why Peter brings up this point in the first place.

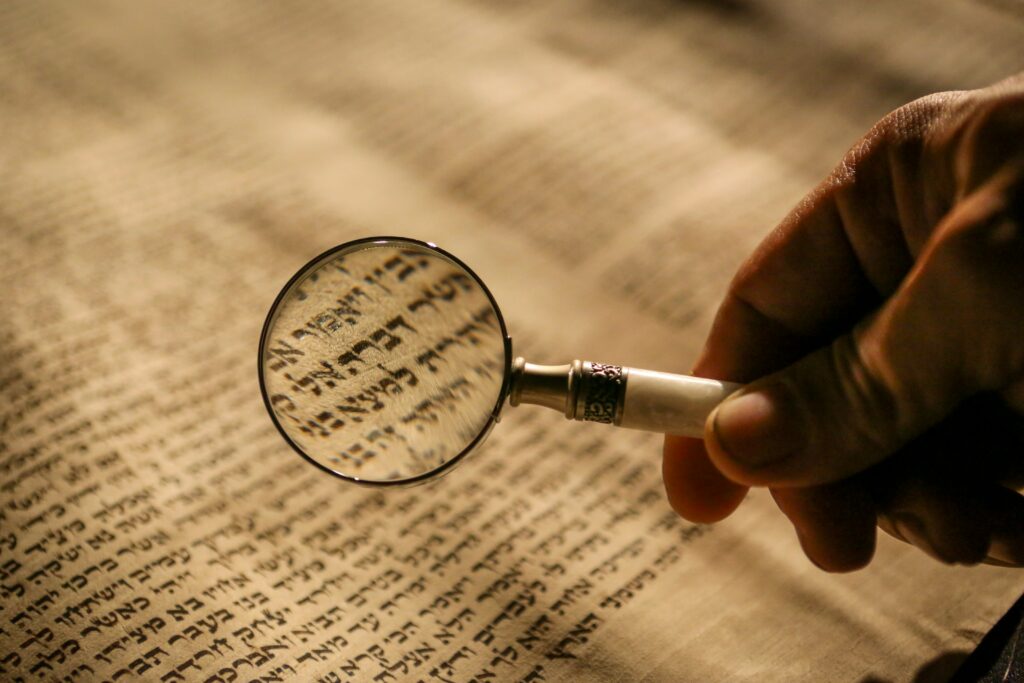

Photo by Mick Haupt on Unsplash