Part 1: Like No One Else | Part 2: Deity 1

In the previous post we considered three passages that explicitly assert that Jesus is God. Let’s try to get to four more here.

- whose are the fathers, and from whom is the Christ according to the flesh, who is over all, God blessed forever. Amen (Ro 9.5).

In the context (Ro 9.1-4) Paul is talking about the privileges Israel has had in God’s plan. Here he climaxes that list by saying that the Messiah is biologically an Israelite. And then he says that this person is “over all, God blessed forever.”

There’s a little wrinkle in this one too. The original manuscripts of the Scripture had no punctuation and no spaces between words, so later copyists and translators had to do a little interpretation. Here the Revised Standard Version splits the words into two sentences:

to them belong the patriarchs, and of their race, according to the flesh, is the Christ. God who is over all be blessed for ever. Amen.

Now, that’s theoretically possible. But I reject that rendering outright, for a fairly simple reason: the RSV has turned the ending into a benediction, and that’s not the form that benedictions typically take. In Greek it’s common to emphasize a word by putting it at the front of the sentence. In a benediction, then, you typically put the word “blessed” first (Lk 1.68; 2Co 1.3; Ep 1.3; 1P 1.3); that’s the whole point of the benediction.

Here, however, Paul puts the word “God” first—because he’s emphasizing it. “This Jewish man, this ordinary-looking guy? He’s [pause for effect] GOD!!!!”

Like the Jehovah’s Witnesses in John 1.1, I think the RSV translators are showing their (liberal) theological bias here. The New RSV (1989), FWIW, let the deity of Christ show through by translating the passage as a single sentence.

- looking for the blessed hope and the appearing of the glory of our great God and Savior, Christ Jesus (Ti 2.13 NASB95).

I’ve used the NASB here because it renders the underlying Greek more clearly than the KJV, which is slightly ambiguous (the great God and our Saviour—is that one person or two?). The Greek construction unambiguously indicates that the two nouns are the same person. This construction is called “the Granville Sharp rule,” named for the nineteeth-century African missionary who discovered it. The KJV translators can hardly be faulted for not knowing about the rule in 1611; they translated it literally, which is just fine.

- But unto the Son he saith, Thy throne, O God, is for ever and ever: a sceptre of righteousness is the sceptre of thy kingdom (He 1.8).

This is a quotation of Psalm 45.6—Thy throne, O God, is for ever and ever: The sceptre of thy kingdom is a right sceptre.

The JWs render this “God is your throne.” Again, as in John 1.1, this is a possible rendering of the Greek, but not the most likely one. Dan Wallace, who is perhaps the leading living Greek scholar, and the author of the most highly recognized Greek grammar (the 800-page Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics), thinks “God” in this verse should be translated as direct address for four reasons (p 59), of which I’ll mention just two. First, the Hebrew accenting of Psalm 45.6 indicates that God is being addressed; and second, the Greek sentence here (He 1.7-8) is constructed as a contrast (“on the one hand … on the other hand”), and in the JW translation that contrast completely disappears. (“On the one hand, the angels are merely his servants; on the other hand, the Son is also under God’s authority.”)

- And we know that the Son of God is come, and hath given us an understanding, that we may know him that is true, and we are in him that is true, even in his Son Jesus Christ. This is the true God, and eternal life (1J 5.20).

One more little wrinkle. The verse is clearly referencing two persons: the Father (“him that is true”) and “his Son Jesus Christ.” Which of those two persons is John calling “the true God”?

The Greek doesn’t help us here; both “the true one” and “the Son” are masculine nouns, and the masculine pronoun “this one” could refer back to either. Both possible antecedents are near enough that either one is reasonably possible. But since “Son” is the nearer one, then I would prefer it, all other things being equal.

That’s my list of seven passages that explicitly call Jesus God. Next time we’ll look at another category of biblical evidence.

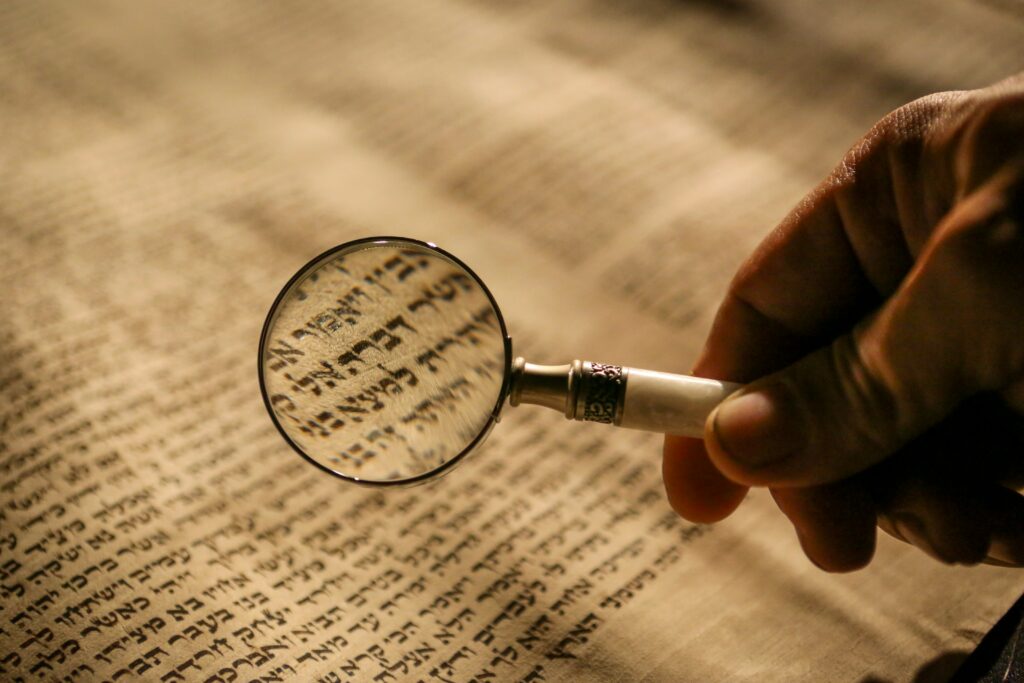

Photo by Aaron Burden on Unsplash

Part 4: Deity 3 | Part 5: Deity 4 | Part 6: Deity 5 | Part 7: Deity 6 | Part 8: Deity 7 | Part 9: Deity 8 | Part 10: Deity 9 | Part 11: Humanity 1 | Part 12: Humanity 2 | Part 13: Humanity 3 | Part 14: Humanity 4 | Part 15: Unity 1 | Part 16: Unity 2 | Part 17: Unity 3