Part 1: Background | Part 2: Loyal Love | Part 3: Chance | Part 4: Abundance | Part 5: A Plan

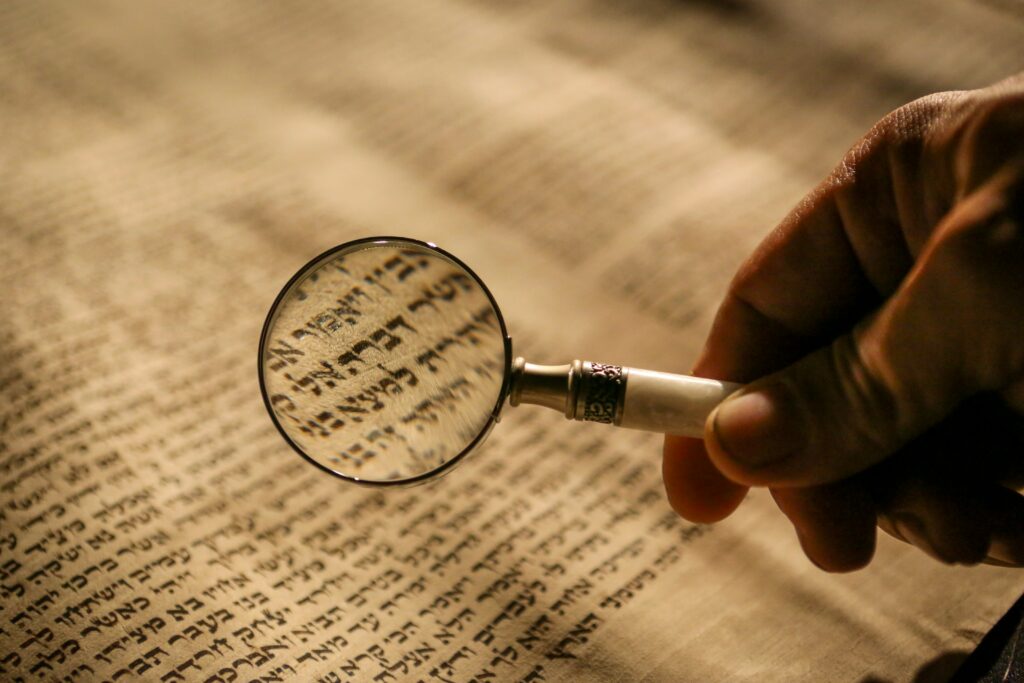

After harvest comes threshing, and then winnowing. Threshing is the torturing of the harvested stalks so that the kernels, which are the whole point, are physically separated from their husks and from the cut stalks; winnowing involves tossing the kernels into the air so that the wind will blow away the lighter husks, allowing the weightier, unmixed kernels to fall to the ground. “A threshing floor was a stone surface in the fields where the harvest husks were crushed and the grain sifted from the chaff” (HCBC). Winnowing would take place at the nearest point to the field where a stiff breeze was available, typically at a high point.

With the harvest over, and threshing in progress, Naomi, the mother, recognizes her responsibility to find a husband (“rest”) for Ruth (Ru 3.1-2). She knows that Boaz is aware of their plight, is a near relative, and is of means. This can’t all be just a coincidence, can it?

But the harvest has taken a few weeks, and Boaz hasn’t indicated any inclination to do anything more than be generous with his grain. Naomi thinks he needs a nudge.

This was not culturally inappropriate, nor was it meddlesome. Israelites in financial peril from widowhood were entitled to claim a kinsman redeemer (Dt 25.5-6). We call this “levirate marriage” (from the Latin levir, brother-in-law), and the nearest relative was obligated if able. Other responsibilities included avenging a clan member’s murder (Nu 35), redeeming clan land (Le 25.23-28), and redeeming a clan relative from debt slavery (Le 25.35-55) through an interest-free loan (Le 25.35ff) or provision of labor (Le 25.39ff) (AYBD).

All of this legal provision is to remind Israel that God is the ultimate kinsman-redeemer of Israel (Is 63.16; 54.5), based on chesed, loyal covenant love. (The word has appeared in Ru 2.20 and will appear again in Ru 3.10.)

With all this in mind, and knowing that a feast was commonly held when the harvest work was finished, Naomi decides that now is the time. So she shares her plan with her daughter-in-law.

Ruth is going to make herself presentable, as they say, and go to the threshing floor. There she’ll be able to watch the men eat and then settle in for the night, sleeping by the threshed grain to protect it from thieves and from scavenging animals. After Boaz settles in, when it’s dark, she will go and lie down at his feet.

And then, Naomi is reasonably certain, good Boaz will continue to do the right thing, even if it’s more of a commitment than has been required of him so far.

Some interpreters have suggested that something sexual was occurring here. That idea directly contradicts the characters of Ruth and Boaz and the direction of the plot. First, Naomi sends Ruth into that risky situation precisely because she knows that Boaz will protect her; he has already demonstrated that out in the field (Ru 2.9, 22). And Ruth has demonstrated her noble character as well in following Naomi to Bethlehem and in laboring in the field; Boaz will shortly say that she is “a woman of excellence” (Ru 3.11).

Further, the direction of the plot argues against premature sexual behavior. We’ve noticed a recurring theme in the story:

- It begins with Ruth placing herself in the care of not only Naomi, but Naomi’s God (Ru 1.16).

- Boaz notices and comments on what she has done: “under whose wings you have come to trust” (Ru 2.12).

- Boaz is using here an image from his culture and history. In giving Moses detailed instructions for the construction of the Tabernacle, he has required that above the gold covering of the Ark of the Covenant—the “mercy seat”—are two angelic creatures, cherubim, under whose wings God will meet his people in the person of their high priest on the Day of Atonement. As Moses delivers his farewell address to the people of Israel, he refers to this image:

- As an eagle stirreth up her nest, fluttereth over her young, spreadeth abroad her wings, taketh them, beareth them on her wings: So the Lord alone did lead [Jacob and the people of Israel], and there was no strange god with him (Dt 32.11-12).

- In a few minutes, when Ruth repeats to Boaz what Naomi has instructed her to say, she will reference this image: “Spread your wings over your handmaid” (Ru 3.9).

Against all this background, hanky-panky? Ridiculous. I don’t think so.

Ruth trusts Naomi’s judgment and obeys explicitly.

The outcome next time.

Photo by Paz Arando on Unsplash