Part 1: Introduction | Part 2: Flexible Evangelism

In what ways can we accommodate a culture in evangelistic efforts, and in what ways can we not? How do we know? Where do we draw the line?

This is not just a matter of personal taste: “I don’t like that” or “That makes me uncomfortable” or “That offends me.” And it’s not just a matter of whether a cultural practice seems strange to us. It’s the very nature of cross-cultural work that practices will seem strange until you know why those practices exist—and perhaps after you know as well.

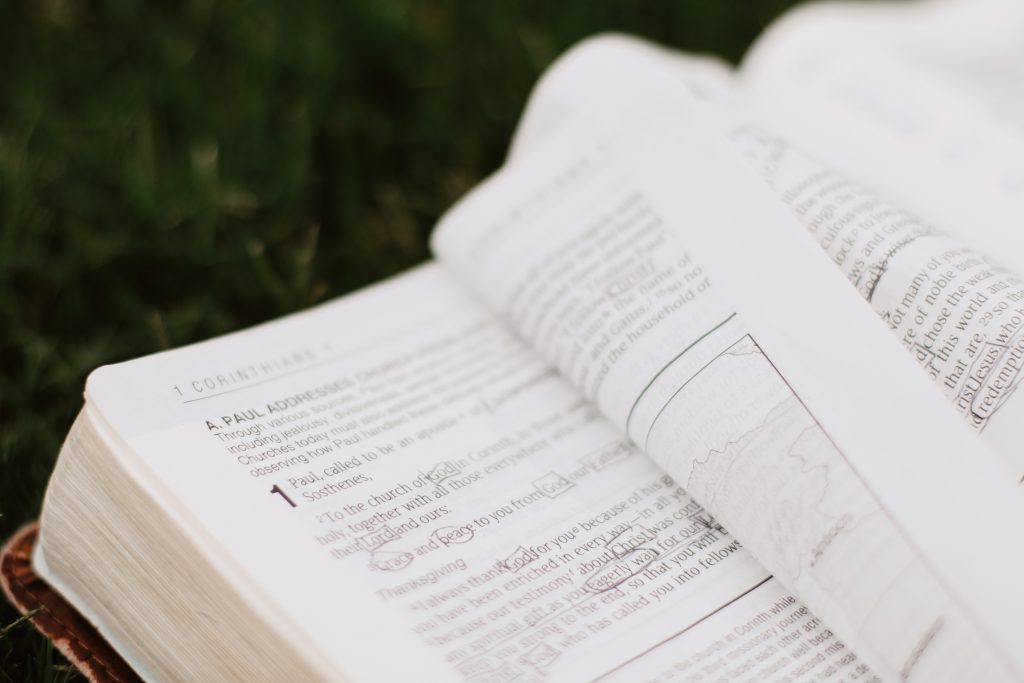

As always, we Christians take our directions from the Scripture, because it is the Word of God, inerrant and authoritative. Does the Bible have anything to say about how we interact with our culture?

You bet it does. While it begins with a clear affirmation that all humans are created in the image of God (Ge 1.26-27), it also affirms that all humans have sinned (Ro 3.23). As a result, when sinners form cultures, those cultures reflect the brokenness that sin invariably brings.

Some cultures may seem more “broken” to us than others, but I suspect that much of that sense springs from our bias toward our own culture. Some cultures require very little clothing; some are in constant warfare with neighboring tribes; some are tyrannical and abusive. But our culture is broken too, given over to the pursuit of wealth and power, worshiping at the false altar of entertainment, and in constant warfare with neighboring political tribes.

The Bible doesn’t use the word “culture” except in the more paraphrastic versions such as The Message and the Passion Translation. (The King James uses it in the Apocrypha, in 2 Esdras 8.6, but in a different sense.) But there is a word in the Bible that closely parallels the concept. The Bible speaks often of “the world,” and some of those uses mean something pretty close to “culture.” But the biblical sense is uniformly evil, whereas today “culture” includes many things that are not evil at all. But the Scripture does identify some things to avoid in “the world” (1J 2.15-17):

- The lust of the flesh

- The lust of the eyes

- The pride of life

When a culture embodies or embraces these things, we evangelists cannot adopt them as a vehicle for spreading the gospel.

The Lust of the Flesh

When we hear this expression, we tend to think of sexual lust—probably because our own culture is pervasively pornographic. And yes, the incitation of sexual desire outside of marriage is evil, not something we can endorse or accommodate.

But “the flesh” includes more than just sexual matters. “Lust of the flesh” includes anything that caters to sinful physical desires.

- Gluttony is such a lust—and I’ve been in other cultures where their single observation about us Americans is that we all eat too much.

- Laziness—the desire for an unjustified amount of rest—is also catering to an inappropriate physical desire. I suppose that would include not just lying in bed all day, but overdosing on entertainment or scrolling on social media for hours.

A clue, I think, is that if you can’t stop it, then it’s out of control.

Next time, we’ll finish the list and attempt to draw out some governing principles.

Photo by Joseph Grazone on Unsplash