When I was a boy, my Dad worked for a politically conservative speaker’s bureau. As a result, I got to meet a lot of interesting people when they came to town to give a speech. There was Gen. Robert Scott, WW2 fighter pilot and author of the book God Is My Co-Pilot, who sat at our dinner table and told wonderful story after wonderful story. There was Maj. Pedro Diaz Lanz, compatriot of Fidel Castro and chief of the Cuban Air Force, who defected and told horrific stories of repression in Cuba. There was Slobodan Draskovich, who hijacked a commercial flight to get out of Communist Yugoslavia, and who thought the wire leading to the electric blanket in our guest bedroom was evidence that someone was trying to kill him.

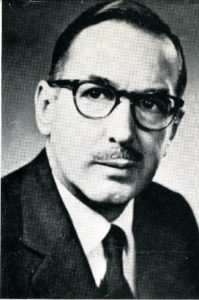

But my favorite was Hilaire du Berrier, a farm boy from North Dakota who was expelled by Pillsbury Military Academy (later the campus of Pillsbury Baptist Bible College) a month before graduation and eventually ran off to be a soldier of fortune. He fought against the Fascists in Ethiopia and spied against the Communists in the Spanish Civil War, then spied against the Japanese in Shanghai during their occupation of China. (As part of his cover he rented a room to a woman who later became one of Mao’s wives and was eventually disgraced as leader of the Gang of Four.) Eventually captured by the Japanese, he bore the scars of torture during their interrogation.

In short, he had a lot of stories to tell.

In town for a speaking engagement, he stayed at our house for 3 days in the spring of ’63.

I was a hyperactive kid, a complete pain in the neck.

He took an interest in me.

He showed me how to make a different kind of paper airplane. He told me stories about his idol, Napoleon. (Hilaire’s real name was Harold; he changed it to Hilaire in honor of one of Napoleon’s generals.) He took me to an office-supply store and showed me where they sold liquid rubber, the kind you use to make tear-off pads of paper. It was pink and had a distinctly pungent smell. He showed me that you could take a 3-dimensional object—he had a metal eagle that he’d gotten off a Napoleonic dispatch case, and why he had it with him on that trip, I’ll never know—and cover it with several layers of liquid rubber to make a mold. Then he showed me how to mix plaster of paris (is that French?), pour it into the mold, insert a wire in the back, and make an exact copy of the object, paint it (with gold paint!), and yield a pretty cool wall plaque. He took a little plaque I already had, with the Cub Scout oath on it, and we made a copy of that too.

I was a lot older when I realized that he had been teaching me spycraft.

He had a lady friend in our town—she was the host of the local Romper Room show—and incited me to come along on a dinner date to act as escort for her daughter. He instructed and rehearsed me to present my “date”—I was 8—with one of our cool gold-painted plaster eagles and induct her into the Society of Napoleon. We had a fabulous time at a fancy restaurant in Spokane. (In those days, there weren’t a lot of those.)

Hilaire was an artist as well; he’d done commercial art in Chicago before running off to chase adventure. He told me I should write a book; he laid out a characterization for me, presenting each of my family members as an interesting animal: Mel Mouse, Pauline Pony, Betty Jeanne Jackrabbit (though he misspelled her name), Kathy Cat, and, of course, Danny Dog. I should write The Story of Danny Dog and His Friends, he told me, and he said he would wait expectantly for me to send him a copy when it was published.

A few days later, having returned from the speaking tour to his apartment in New York, he wrote me a letter to let me know he was still thinking about me, and to encourage me to get to work on The Book.

He lived another 40 years, writing an international intelligence subscription letter called HduB Reports, eventually dying in his 90s, a tax exile in Monaco.

I’ve never forgotten the time he took during those 3 days to reach out to a painfully energetic boy, giving his attention to a kid who needed direction, planting ideas in me that I have gone back to as an adult and that I remember well now more than 50 years later.

Thank you, Hilaire. I’m grateful.

Henry Shirah says

“I was a hyperactive kid, a complete pain in the neck.”

And as an adult????

Yuk, yuk. My resistance failed.

Rachel Larson says

Did you write that book?

Dan Olinger says

Nope. But the Romper Room lady started writing children’s books in her 70s.

Mike Bryant says

Very interesting article